Expectations of the nurse teacher’s role in clinical placements – a literature review

The nurse teacher has a fragmented and unclear pedagogical, academic, relational and innovative role.

Background: The role of the nurse teacher (NT) in clinical placements is characterised by the expectations of students, placement supervisors, the educational institution and not least the NTs themselves. In general, the work of the NT nowadays has less focus on clinical teaching and more on formal teaching and new research requirements. The NT’s role in clinical placements is therefore often described as unclear and poorly defined, and as qualitatively fragmented.

Objective: To shed light on how the NT’s role in clinical placements is described in recent research.

Method: Integrative literature review of findings from eleven research articles: quantitative (n = 6), qualitative (n = 3) and mixed methods (n = 2).

Results: We identified four main categories in the analysis: pedagogical, academic, relational and innovative roles, with nine associated subcategories. The NT’s pedagogical role involves supporting the students in their learning process by linking theory to clinical practice. Furthermore, it is expected that NTs help supervisors with pedagogical challenges and ensure that the clinical and formal requirements in student assessments are met. In the academic role, the NT is pivotal in the efforts to stimulate learning through reflection and critical thinking in order to help the student see the link between the educational and clinical setting. The relational role involves helping students and supervisors in challenging situations, conducting assessment interviews and serving as a bridge-builder between the educational and clinical setting. The innovative role challenges the NT’s ability and skills in the use of new digital technology and new learning methods with a view to improving student learning.

Conclusion: The role of the NT is multifaceted. Consequently, support and facilitation are needed from the educational organisation as well as optimisation of the collaboration with the clinical setting in order to safeguard and stimulate the students’ learning process and help the placement supervisors resolve pedagogical challenges.

Introduction

The NT’s role in clinical placements is described as complex and constantly changing (1). The role has changed on the basis of a national and European perspective in line with quality reforms and new curriculum frameworks (2, 3). Despite reforms and discussions, research shows (4) that NTs still have an important role to play in promoting students’ learning process and professional development.

In 1981, nursing education in Norway was part of the university college system (5). Towards the late 1990s, the Bologna process was set in motion, which led to nursing education being incorporated into the European Credit Transfer System (ECTS), with a view to promoting the mobility of nurses across national borders (3).

Fifty per cent of a bachelor’s degree in nursing is spent in clinical practice. Successful completion of the degree qualifies students as registered nurses and gives them a formal professional qualification (6–8). In this process, NTs were expected to carry out academic work within research and professional development. They were also subject to the traditional expectations linked to the teaching and follow-up of students in clinical practice. NTs were given an advisory, collaborative and supportive role in relation to placement supervisors, who have the day-to-day task of supervising the students in clinical practice (9).

Nowadays, the NT’s role has less emphasis on clinical patient work and staying apace with developments in clinical practice and more on new requirements for formal teaching, research and publication. These changes now guide NTs’ priorities (10).

We define ‘nurse teacher’ as the professional at the educational institution who is the link between the educational and clinical setting. This person also helps to address pedagogical and professional issues and is jointly responsible for assessing the student (11). We use the definition of ‘role’ in the sense of the sum of expectations and norms linked to a specific position or function (12).

The NT’s professional role carries expectations related to knowledge and theoretical insight that must be demonstrated in clinical practice. These expectations are partly created by the NTs themselves, but also stem from the educational institution, registered nurses (RNs) in clinical practice and students. The NT is faced with conflicting pressures between their own and others’ expectations of what is the correct role behaviour (12). These extensive expectations from various parties can explain why the NT’s role in clinical placements is described as unclear, poorly defined (1, 13) and qualitatively fragmented (14, 15).

The NT’s role in clinical placements varies depending on which clinical placement model is applied. The NT may be employed in the clinical field or in an educational institution, or they may split their work between both of these settings. In most European countries, NTs are employed at university colleges or universities under the job title ‘nurse teacher’ (10, 16), while Ireland, the UK and the United States use the term ‘lecturer practitioner’ (LP) or ‘nursing educator’. These roles are filled by RNs working in hospitals with students, and their main responsibility is supervising the students (17).

Combining clinical and educational roles in joint appointments across both settings has been tried in Norway and is considered positive, particularly for providing support for placement supervisors (18). The NT meets expectations of clinical credibility, but in most European countries, NTs are no longer employed in clinical practice (19). Students believe that the NT has little bearing on their learning in clinical practice and that the NT’s clinical competence is limited and not based on real-life clinical experience (20).

Expectations of the NT’s competence

The role of the NT in clinical placements and the formal qualification requirements vary from country to country. The presence of NTs in clinical practice has decreased in several European countries, and in some countries, the students have no interaction with them at all in clinical practice (20, 21). Research shows that there is no consensus on the minimum competence requirement or the role of the NT in clinical placements. The majority of NTs have a master’s degree (19, 22), and they are expected to have competence in pedagogics, research, nursing practice, ethics and management (9, 23).

The World Health Organization (WHO) (24) defines the NT’s core competence as the ability to adapt, design and use tools for assessing and documenting clinical practice, and to ensure use of appropriate methods of assessment that facilitate achievement of learning outcomes. The NT must also encourage reflection and self-assessment of skills and provide constructive feedback.

The European Federation of Nurse Educators (FINE) (25) suggests that the NT’s core competence be divided into four areas: academia, research, clinical practice and management. The National League for Nursing (NLN) in the United States (26) believes that those who train nurses should have a doctorate. According to a European literature review (14), only 4–12% of recently appointed university lecturers in nursing have a doctorate, and having a doctorate does not automatically mean they have pedagogical competence.

A Finnish literature review showed that the NT is expected to use methods that facilitate the learning process and transfer theory to practice, combine traditional clinical practice interaction with innovative digital methods and promote a good learning environment (23). In a Norwegian qualitative study, the NTs believed that supervision is the most important competence for following up students in clinical practice (10).

Two Finnish qualitative studies of various study programmes in health-related subjects showed that the NTs saw themselves as a mentor, with the emphasis on a formative assessment of students’ development and learning (9). The students rated their own competence and goal achievement higher if the NT’s competence was high (4). A Norwegian report from 2018 (27) shows that students feel that the NT helps them to see the link between theory and practice and to gain an understanding of the subject.

Earlier research identifies the experiences of placement supervisors in supervising nursing students in clinical practice and the challenges they face (28, 29). Students’ experiences and perceptions of the field of practice as a learning arena have also been explored (30). After the introduction of nursing in higher education, the role of the NT in clinical placements came into focus in several studies. Much of the discussion touched on the NT’s identity and role in clinical placements and on how the role should be influenced by academia (22).

In contrast, there has been little research on NT’s experiences in recent decades, despite new requirements being imposed. Our own experiences and this literature review indicate an increase in expectations and requirements in terms of the NT’s role in clinical placements. We want to gain an insight into what the expectations mean for the role, and whether these expectations shed light on the challenges faced by NTs in clinical placements in Western countries.

Objective of the literature review

The objective of this literature review was to shed light on how the NT’s role in clinical placements is described in recent research. We aimed to answer the following research question:

‘What characterises the expectations of the nurse teacher’s role in clinical placements?’

Method

The review is designed as an integrative literature review (31). The aim is to summarise previous empirical and theoretical literature to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a particular topic or phenomenon. The method was developed by Whittemore and Knafl in 2005 (32) and allows for different research methods to be combined, making it the broadest type of literature review.

The method can promote conceptual and theoretical development and has played an important role in evidence-based practice in the nursing profession (31). The method consists of five steps: problem formulation, data collection, evaluation of data, data analysis and presentation of results.

Search strategy

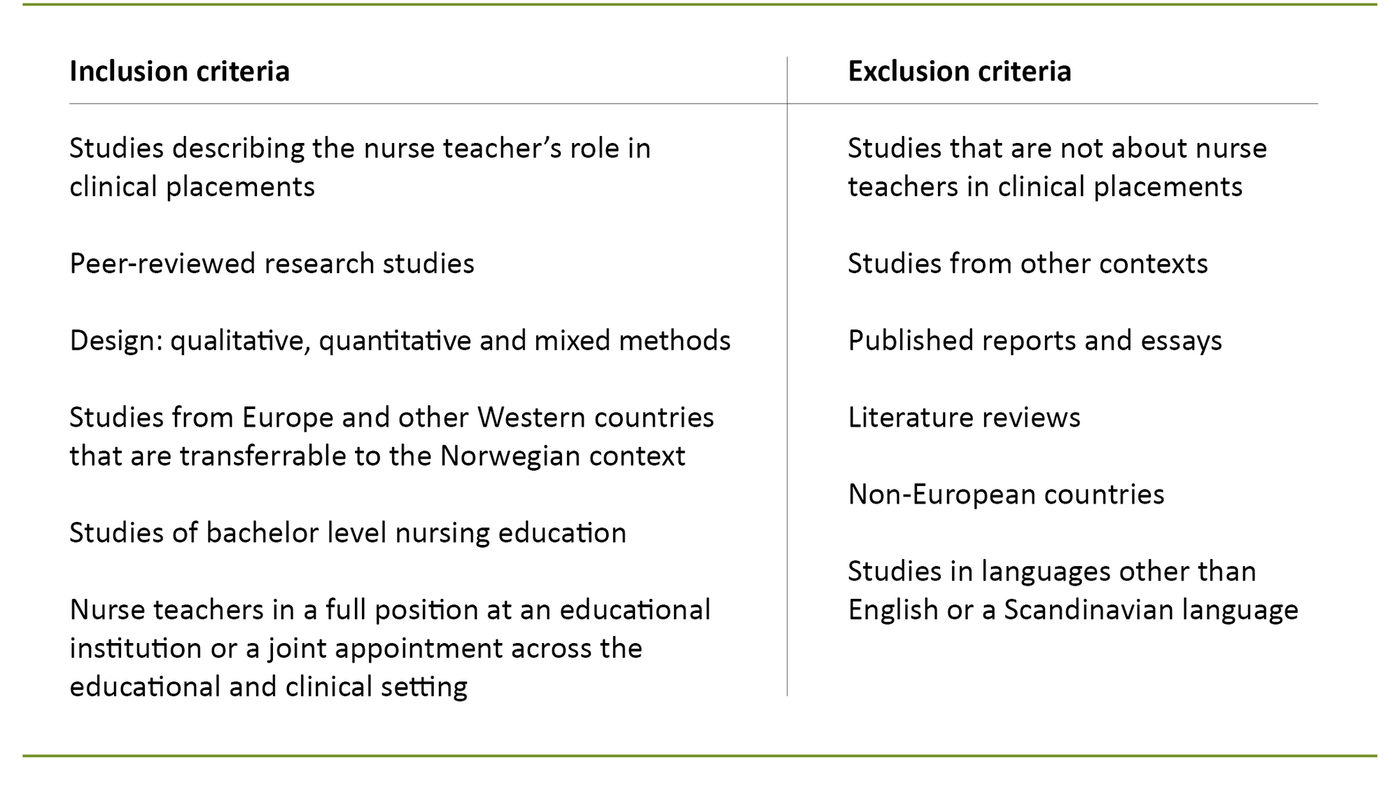

Based on the study’s objective and research question, we conducted an initial broad search with the help of a librarian from Oslomet – Oslo Metropolitan University on 20 January 2020. This search helped us to identify relevant knowledge about previous research as well as keywords and terms, and to refine our research question and the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1).

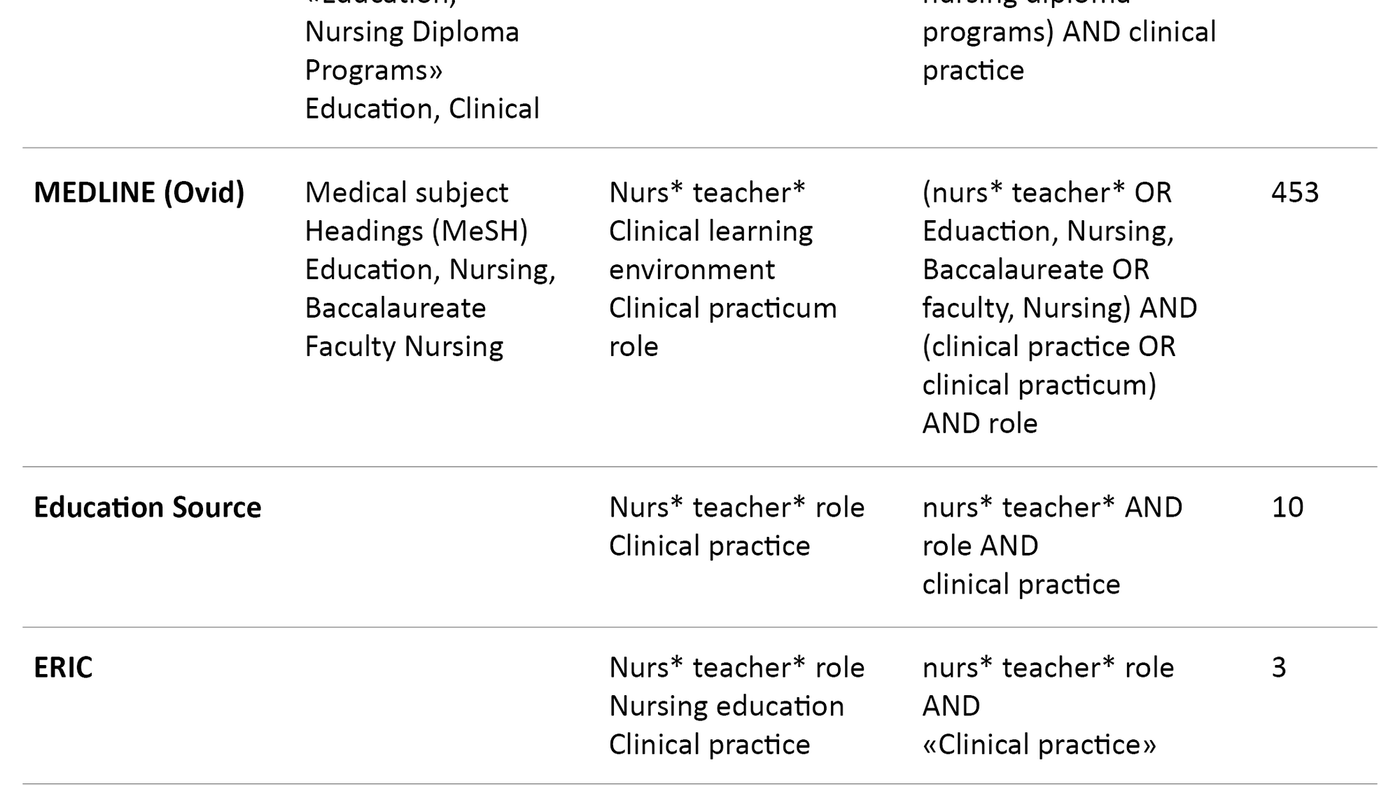

During the initial search, we discovered that much of the research on the NT’s role was conducted in connection with work carried out before and after the Bologna process was implemented. We devised a new search strategy for the second search with a librarian on 27 February 2020. We defined search terms and keywords and tailored the search strategy to the various databases (Table 2).

We searched five databases that cover the nursing profession and the educational dimension of the field of practice: CINAHL and MEDLINE cover the nursing profession, ERIC and Education Source cover relevant education-related themes at all levels of education and all specialist areas within pedagogy, and Web of Science includes journals in the natural sciences, social sciences and the humanities.

We started the literature selection by reading titles and abstracts and then the full text of selected articles. Our main focus – the role of the NT in clinical placements – determined what literature was included. The literature described the role from the perspectives of the NT, the student and the supervisor. It also described what has characterised the NT’s role since the implementation of the Bologna process. We therefore limited the search to research articles published after 2010.

We included individual studies with a qualitative or quantitative design as well as individual studies with mixed methods and original results that were relevant to the Norwegian context.

Although we limited the search to literature published after 2010, we included two studies from 2009 that shed light on the development of the NT’s role in clinical placements. We identified the first study, from 2009 (33), in the first broad search. The second study (34) was found in the reference list of Løfmark et al. (35).

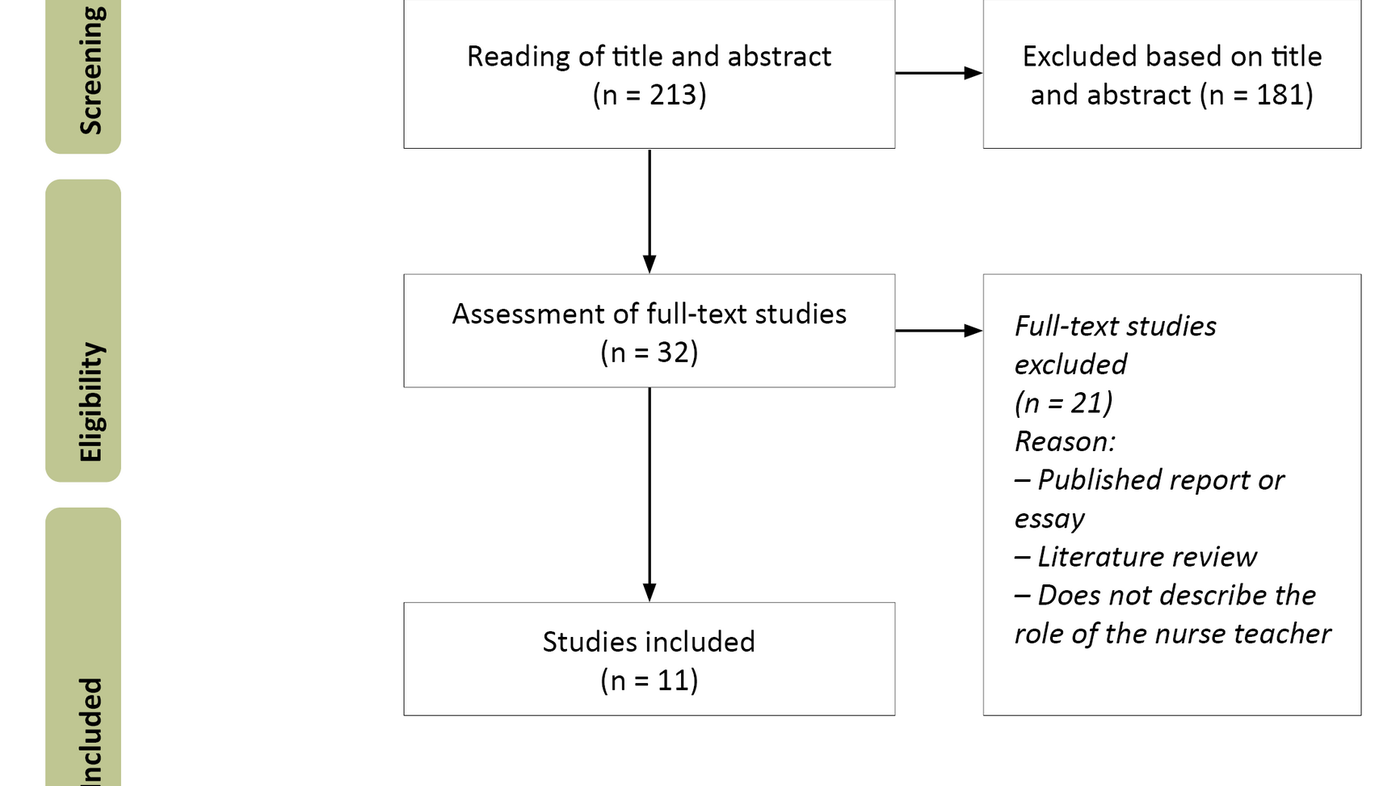

Both authors participated in the search process and selection of the literature, and both also read the research articles. We actively searched the reference lists of the selected literature to identify other relevant research. The result is described above. The search process is presented in a PRISMA flow diagram (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) (Figure 1).

Analysis

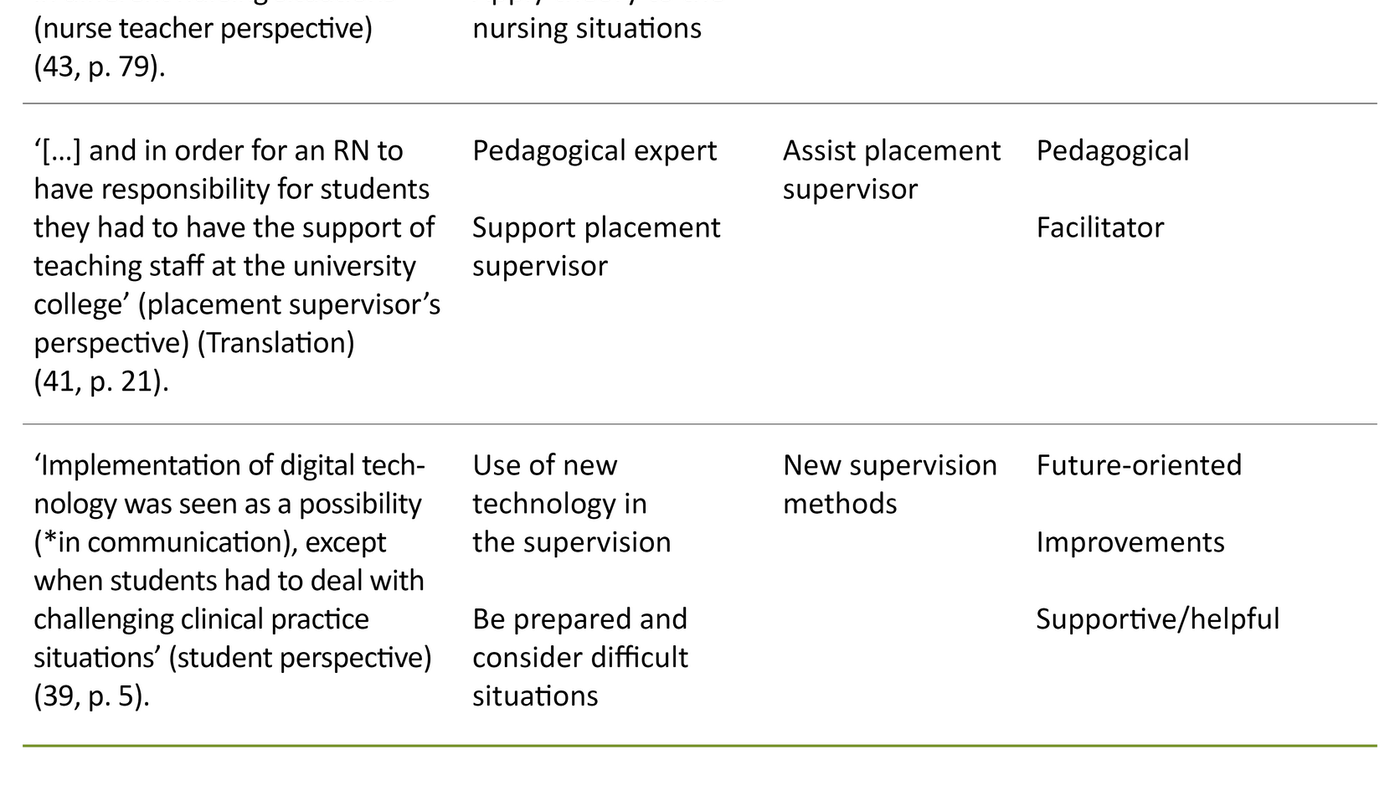

After the selection process, we read and analysed the text of the articles based on the approach outlined in Whittemore and Knafl (32). The data used in the analysis were extracted from the results of the articles. The analysis method had three phases: data reduction, display and comparison of data. In the first phase, we organised and colour-coded the material according to the research question.

In the second phase, we extracted coded meaning units and systematised these into preliminary categories. In the third phase, we identified similarities and differences as well as patterns and relationships in the data. Table 3 shows an extract from the analysis process.

Data with similar content were grouped together. Categories were developed and then synthesised into corresponding subcategories. In this phase, we received input from colleagues in our research group. We discussed the content of the categories in relation to the literature review’s objective and research question. Four main categories of the NT’s role emerged in the analysis.

Results

Studies and design

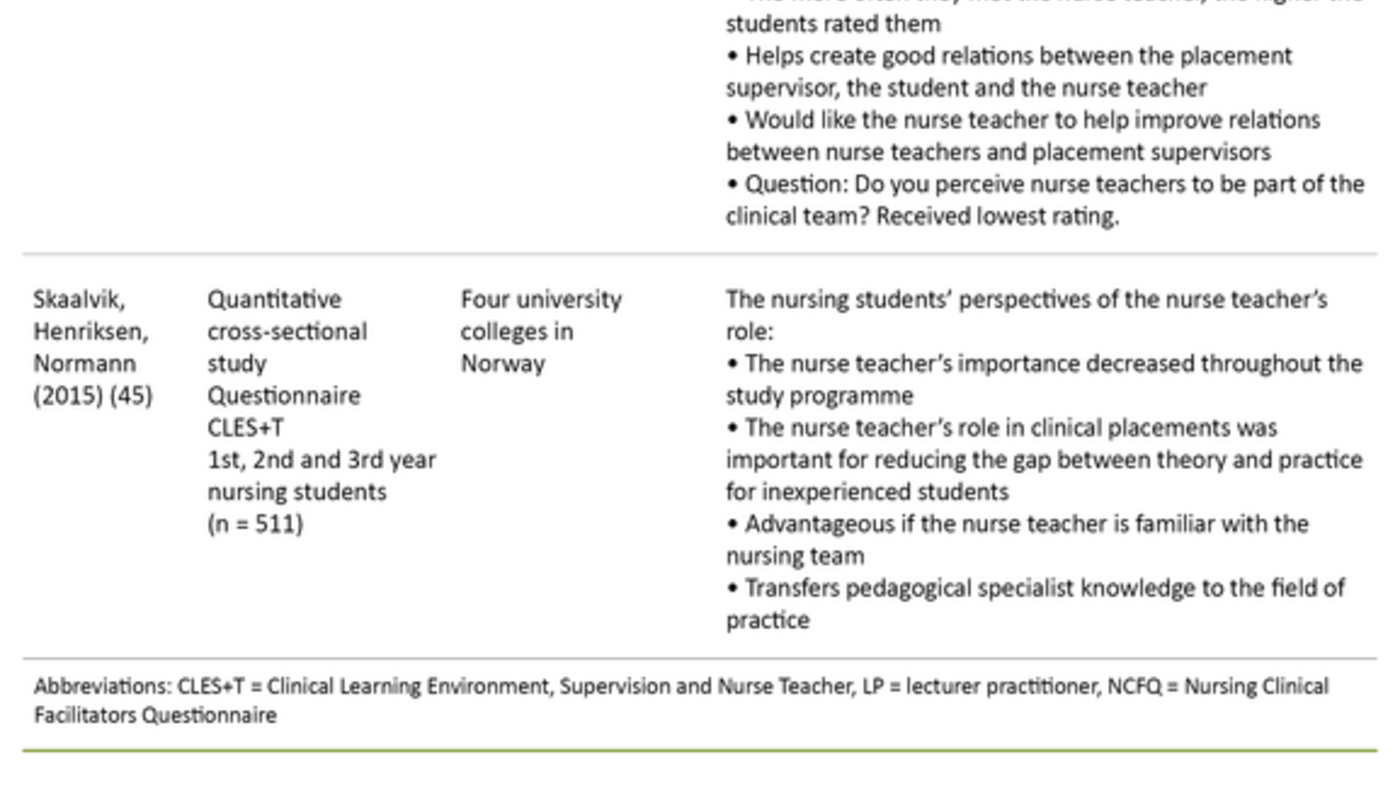

We included eleven research articles from Finland, Norway, Sweden, Ireland and the UK. Most of the articles explore the role of the NT in clinical placements through a study of the perspectives of students (n = 10), placement supervisors (n = 2) and NTs (n = 3). The eleven studies selected used a quantitative (n = 6), qualitative (n = 3) or mixed methods (n = 2) design (Table 4).

The quantitative studies and mixed methods studies used validated mapping tools. Saarikoski et al. (36) developed the Clinical Learning Environment, Supervision and Nurse Teacher Scale (CLES+T), which consists of five subscales. One of the subscales relates to the ‘Role of the nurse teacher (NT) in clinical practice’, and consists of nine items.

These items are divided into three categories that address the NT as the party that facilitates the integration of theory with practice, collaborates with the clinical field and strengthens the relationship between the student, the supervisor and the NT. The Nursing Clinical Facilitators Questionnaire (NCFQ) was designed by the Centre for Learning and Teaching at the University of Technology of Sydney. It was translated into Norwegian and tested in Norway in 2003 (37).

The purpose of the instrument is to measure student satisfaction with the supervision they receive in clinical practice. The original questionnaire consists of 28 questions divided into four sections on pedagogical strategies, supervision practices, the relationship between the supervisor, the NT and the student, and feedback given to the students.

In the qualitative studies and mixed methods studies, the nursing students were interviewed about their experiences and perceptions of the NT’s role in clinical placements and asked to give their reflections on this role. The supervisors and NTs were interviewed on the same topics from their own perspective.

We identified four main categories in the analysis: 1) pedagogical role, 2) academic role, 3) relational role, and 4) innovative role (Table 5). We explain the results in the four categories and nine associated subcategories below.

Pedagogical role

The first main category – ‘Pedagogical role’ – consists of three subcategories: ‘Student support in the learning process’ (33–35, 38, 39, 41, 42, 45), ‘Supervisor support in the supervision of students’ (33, 34, 38, 41, 45) and ‘Accurate and fair assessment’ (38, 40, 41). The NT is expected to help both the student and the placement supervisor to understand the learning outcomes and to reflect with them on how these can best be achieved.

Student support in the learning process

Students’ learning is considered the top priority. In one of the selected studies, the students rated the NT’s supervision in clinical placements the highest, closely followed by the placement supervisor. The NT played a significant role in the students achieving the expected learning outcomes (35). NTs in joint appointments across the educational and clinical setting were more often perceived as part of the clinical team and were described as having a positive effect on the students’ learning in clinical practice (33, 38).

NTs in educational settings had an advantage in that they incorporated their theoretical knowledge into the clinical context (34, 45). This helped the students link theory to practice, which in turn promoted a good learning environment (39, 41, 42, 45). In addition, these NTs are familiar with the content of the learning outcomes and can suggest relevant learning situations to operationalise these (34, 38, 42).

NTs in clinical settings were better at operationalising the learning outcomes in the clinical context than teachers who only worked at an educational institution. This aided the students’ understanding of the link between theory and practice (38). The collaboration between the NT and the placement supervisor is a crucial part of the learning process (45).

Supervisor support in the supervision of students

NTs contribute pedagogical expertise and facilitate the relationship between the student and the placement supervisor (45). They also provide support to placement supervisors in the event of pedagogical challenges (34, 38).

The placement supervisors feel that the NT’s presence relieves part of their responsibility and aids learning. When they are present in clinical practice, NTs support the placement supervisors in assessing students’ learning outcomes (41). A similar approach was taken by NTs in clinical settings, who indirectly supported the students by supporting the placement supervisors (33).

Accurate and fair assessment

Both students and placement supervisors need guidance and support from the NTs in order to ensure that the assessment process is carried out correctly, relevant criteria are met and the correct procedure is followed (41).

Findings showed that NTs consider their involvement in the final assessment to be the most important, and the placement supervisors and students agreed. However, the same study showed that the placement supervisors and the NTs considered the final assessment to be fairer and in accordance with the learning activities, while the students only partly agreed with this claim (40).

NTs from educational settings were present at the mid-term assessment, but not always at the final assessment. Sometimes the assessments were performed with only with the placement supervisor and student present, despite the NT’s formal responsibility (38).

Academic role

The second main category – ‘Academic role’ – consists of two subcategories: ‘The research aspect of education’ (43, 45) and ‘The nurse teacher in the role of researcher’ (43). NTs are expected to help ensure that students develop critical skills through asking questions and reflecting on their own points of view. NTs should also be the driving force behind research work and the publishing of findings.

The research aspect of education

The academic role is closely linked to the pedagogical role. When the NT encourages the student to reflect on their theoretical knowledge and incorporate it into their learning process, the gap between theory and practice can be reduced (43, 45).

Similarly, by adopting an evidence-based approach to practice, the student can be trained to recognise the connection between, for example, ethical issues and the impact of ethics on practical situations. The NT links theory to learning situations in order to facilitate the learning process whilst also promoting a research-based culture in clinical practice. Research shows that NTs did not always trust that the placement supervisors applied theory in the supervision work, but instead used their experiences from clinical practice (43).

The nurse teacher (NT) in the role of researcher

In the selected studies, there was seldom any collaboration between the NT and the clinical field in relation to research and professional development. NTs took time to reflect with the students, but little time was spent on collaborative research and development. Lack of time and organisational support prevented NTs from carrying out their three main tasks: teaching, research and development. It was emphasised how, ideally, research should be conducted in collaboration with the clinical field (43).

Relational role

The third main category – ‘Relational role’ – consists of two subcategories: ‘Bridge-builder between education and clinical practice’ (33, 34, 38, 39, 42–44) and ‘Facilitator in the placement supervisor-student relationship and the placement supervisor-NT-student relationship’ (34, 38 , 39, 42, 44, 45). The student’s relationship with the placement supervisor is important for learning. A good collaboration between the educational and clinical setting is promoted if the NT is familiar with the clinical placement institution.

Bridge-builder between education and clinical practice

Being prepared was important for the students’ achievement of the learning outcomes and professional development during clinical practice. The information provided by the NT about the clinical placement institution and the learning opportunities helped prepare the students (39). The students did not perceive the NT from the educational setting as affiliated with the clinical placement institution (34, 38).

However, NTs in joint appointments were often held in high regard as part of the clinical placement institution. Their knowledge and skills in clinical practice were highly valued by the students. As the link to the educational institution, they were also able to share their experiences from nursing practice in the clinical field and explain changes (33, 42, 43).

By combining the clinical and educational roles in joint appointments, NTs are able to follow the students from the classroom into clinical practice, where they can reflect together (43). Regardless of whether the NT holds a joint appointment or is solely employed at a university or university college, findings show that it is important to safeguard the collaboration between the educational institution and the clinical field (38, 43). Who the students view as a role model in the profession varies: the NT (39) or the placement supervisor (44).

Facilitator in the placement supervisor-student relationship and the placement supervisor-NT-student relationship

Facilitating the best possible relationship between supervisors and students was an essential task for NTs (39, 42), but one that was not always achieved (45). Insufficient interaction with the NT was perceived negatively and was interpreted to mean that the NT was not interested in the student’s progress in clinical practice. If challenges arose, the student felt alone and often had to sort things out themselves (38).

In challenging situations, the student regarded the NT as the one who exercised justice, acted as a mediator and had the courage to intervene (39). Establishing positive interaction and a good relationship between the NT, the supervisor and the student was described as particularly important for addressing student challenges (38).

The more meetings the students had with the NT, the more satisfied they were (34). When the latter was solely employed at an educational institution, the students and NT had the least interaction, but there was more interaction when the NT also worked in the clinical setting (38).

The number of times the NT and student met during a clinical placement varied across clinical placement institutions and countries, from none to four. The duration of the interaction also varied. The students found this interaction valuable (42, 44).

Innovative role

The fourth main category – ‘Innovative role’ – consists of two subcategories: ‘Digital technology’ (34, 39, 43, 44) and ‘New approaches in clinical practice’ (33, 42). Demands for a higher level of research competence, use of digital learning platforms and shorter clinical placements can represent a challenge to the NT’s effectiveness.

Digital technology

Findings revealed that some of the NT’s challenges involved finding new and innovative ways of working. The use of digital tools and simulation in general needs to be improved and more widespread in education (39, 43). In particular, new digital technology can provide more scope to support students in clinical practice (34, 44).

NTs must develop their digital repertoire and competence. Videoconferencing is preferred for assessment interviews if in-person interviews are not possible. The students generally wanted in-person meetings and felt that the NT should have a regular presence in clinical practice. Digital communication should only be used as an aid. In-person meetings help strengthen good relations between the student and NT (39).

New approaches in clinical practice

The students agreed that NTs in joint appointments were well suited to developing the students’ skills. They used nursing–patient situations and acted as mentors. Their own clinical work as part of a joint appointment across both settings gave them greater credibility in the teaching role (33).

A Scottish study (42) presented a new role: practice education facilitator (PEF), which was established by health and education authorities in the UK in 2004. The aim was to strengthen the supervision of nursing students in clinical practice by facilitating professional development and supporting the placement supervisors in this work.

Discussion

The objective of this literature review was to shed light on how the NT’s role in clinical placements is described in recent research. Our aim was to identify the expectations placed on the NT from the perspectives of the student, placement supervisor and NT. The results show that the NT has four different roles in relation to clinical practice: pedagogical, academic, relational and innovative.

The expectations linked to these roles do not necessarily have to conflict with each other; on the contrary, they can complement each other. However, other factors, such as time pressure, workload and poorly defined roles, can mean that the NT nevertheless regards the role as complex, unclear and fragmented (1, 13).

Pedagogical role

The students consider the NT to be an important learning resource in the process of integrating theory and practice. The NT helped students identify learning situations that enabled them to operationalise the learning outcomes (33).

We believe that the NT can be regarded as complementary to the placement supervisor in the light of role theory (12), where the NT and the placement supervisor constitute a ‘pair’, with the reciprocal clarification of roles, both of which must be fulfilled in the best interest of the student. The NT can, for example, take the initiative to introduce theoretical perspectives to ethical and clinical patient situations (43).

The students are entitled to have the assessment of their clinical practice performed in a pedagogical and fair manner and according to current guidelines (38, 40), as well as in accordance with agreements between the clinical and educational settings (14).

The NT undoubtedly plays a special role in clinical placements in connection with assessments (40), as well as in challenging student situations and/or conflicts between the placement supervisor’s dual role as supervisor and assessor (38). In such cases, students often place their trust in the NT as a representative of the educational institution and the formal responsibility that entails (16).

However, research shows that the NT is dependent on the student’s and placement supervisor’s input and assessment in clinical practice (38). It is therefore concerning that the survey of supervisor competence by the Norwegian Nurses Organisation (NSF) (46) shows that less than half of RNs in primary care have a formal supervision qualification, and only around a quarter have allocated time for student supervision.

Findings from the Scandinavian study, in which NTs from the four countries Denmark, Norway, Finland and Sweden were interviewed (43), showed that NTs did not always trust that placement supervisors incorporated theory into their supervision, and felt that it was too strongly based on their clinical experiences. Other research has also pointed to the same criticism (9, 14).

Nursing students and NTs therefore need to increase their knowledge about research and evidence-based practice. Joint development projects between NTs, students and the field of practice that are based on the principles of evidence-based practice can be beneficial for all parties and inspire future research (47). The authorities require those involved in training nurses to adopt an evidence-based approach in order to develop their own pedagogical activities and help improve the quality of education (11).

Increased cooperation is called for in order to ensure nursing students can stay apace with developments and requirements. Furthermore, the NT should contribute to the research and development collaboration with clinical practice in line with the definition of nursing education as an academic study (3, 6).

Academic role

Expectations linked to the role of NT could be considered incompatible with the quality and competence requirements for supervision, relationship-building and nursing competence (10), which are important ingredients for creating a good learning environment. Internationally, there are further requirements for nursing and research competence (24).

Reforms advocated by the Bologna process and other European organisations (7, 8, 25) call for more academic competence. Several studies highlight the need for staff who train nurses to have a doctorate (14, 22). They also emphasise that postdoctoral fellowships are necessary in order to ensure that nursing education is an evidence-based discipline (24).

Whether these are realistic expectations is debatable. Experience as well as national and international research suggest otherwise, given that only 4–12 per cent of recently recruited education and research personnel in nursing were found to have a doctorate (14).

The gap between clinical nursing and the academic approach continues to be discussed and measured (43), and attitudes and assumptions differ. European research shows that the NT’s presence and teaching in clinical placements have decreased, while the academic requirements are increasing (20, 44).

Recent research indicates that the NT’s clinical competence impacts on the students’ approach to knowledge (13). This is juxtaposed with the decreasing opportunities for NTs to be clinical practitioners (4). Research has shown that the constantly evolving nature of the clinical field makes it unrealistic to expect NTs to stay apace of developments in the field (15).

Do educational institutions have something new to offer clinical practice – or is it the other way around (1)? Our findings showed that the NT values student contact in clinical practice, despite their reduced clinical credibility. If clinical credibility is needed, how can the NT develop this? NTs are, after all, required to stay abreast of issues at the clinical placement institution (48).

We believe that observation schemes and flexible working hours are needed, but the prerequisites for implementation must be met. Unfortunately, NTs’ clinical practice priorities often clash with other tasks, with both the organisation and the NTs themselves wishing to stimulate research and publication (43).

Relational role

In the relational role, NTs are in a unique position to assist both the student and the placement supervisor. Several previous studies have shown that a good relationship between the student and the placement supervisor is a prerequisite for a good learning environment (28, 30).

In this context, NTs are expected to support the students in the learning process by facilitating an optimum student-supervisor-NT relationship. They are also expected to ensure that students become acquainted with the clinical placement as a learning arena (39, 41). The NT’s role as a bridge-builder between the educational and clinical setting is an important finding that highlights this.

Our findings show that the NT’s participation in and collaboration with the field of practice is important, but sometimes inadequate (34). Face-to-face interaction between the student and NT is essential for students to receive the follow-up and feedback needed to develop their knowledge, skills and ability to achieve the expected occupational competence within nursing (49).

By helping the student to internalise both critical thinking and the ability to reflect, the NT is giving the student the opportunity to establish important prerequisites for acquiring this occupational competence.

Innovative role

In the NT’s innovative role, the focus is on digital technology and simulation (34, 39, 43, 44). By combining pedagogical methodology with the integration of technology, the NT promotes innovation. Collaboration on simulation and skills training is an example of activities that can link learning situations to learning outcomes and help reduce the gap between theory and practice.

Using technology in skills training is also relevant prior to clinical practice, with the NT contributing to the development of new learning activities that help prepare the student. Use of remote communication varied considerably between the countries in Europe. Only 6 per cent reported that in-person meetings had been replaced by remote communication (44). The findings show that remote communication on its own was considered insufficient for creating a good relationship between the NT and the student (9, 39).

Discussion is ongoing as to whether joint appointments should be a requirement within the education system and/or the clinical field (50). In several countries, joint appointments across the educational and clinical setting have led to more and improved interdisciplinary collaboration. However, good organisational structures and frameworks are needed as well as management support in both settings (18, 49).

Joint appointments represent a resource for both students and placement supervisors (27, 42). This is perhaps the model that should be adopted to a greater extent in the Nordic countries as well, as NTs in joint appointments often receive a better rating for their supervision of students and support for placement supervisors than those who are solely employed at educational institutions (33).

Reflections on methodology

The search strategy was a challenge because of the diverse range of terms used for ‘nurse teacher’ and ‘clinical placement’. We searched for articles where the NT had an approximately equivalent role as in a Norwegian and European context, i.e. either a full position at an educational institution or a joint appointment across the educational and clinical setting. We used the integrative literature review method with the aim of providing rich data about our topic. This method makes it possible to include studies with different research methods (31).

Using different research methods is challenging because of the need to synthesise quantitative and qualitative data. We therefore marked and coded the data material’s quantitative data with explanatory text in the same way as for the qualitative data.

We have tried to be systematic and accurate throughout the search and selection process, but we cannot ignore the fact that we were unable to identify some articles on the topic, despite receiving professional help.

Conclusion

The NT’s pedagogical and academic roles are fundamental to helping the student and placement supervisor to operationalise the learning outcomes. In the academic role, the NT helps to promote learning through reflection. The relational role aids the student in challenging situations in clinical practice and assessment interviews. The NT is also expected to assist the placement supervisor in dealing with pedagogical student-related challenges.

The relational role is also exercised when the NT acts as a bridge-builder between the educational and clinical setting. In clinical practice, the NT is the communication link between the educational institution, the student and the placement supervisor. In the innovative role, the NT is expected to be well-informed about developments in technology and to help develop collaborative projects.

Examples include preparing local curricula in order to address the learning situations in the field of practice, or optimising assessment criteria to ensure that they correspond with formal requirements and what the clinical practice can offer in terms of learning situations. Joint efforts in simulation and case-based training in clinical problem-solving can also stimulate the collaboration between the educational and clinical setting, whilst simultaneously promoting the students’ learning.

There are few findings that shed light on research collaboration and the use of evidence-based practice. This may be an indication that NTs lack crucial competence, particularly in research. The ideal combination of pedagogical, academic and clinical competence is probably difficult to achieve, but also difficult to maintain.

Does the NT need to demonstrate clinical credibility in clinical practice, or can this be supplemented or replaced with up-to-date research, reflection groups and simulation? It is important that these aspects are discussed in the future, and that further and more up-to-date research is conducted on them. The results show that research is also needed into which clinical placement models and forms of collaboration facilitate a high standard and are optimum from the perspective of the NT, the student and the placement supervisor.

We would like to thank Kari Toverud Jensen, head of the Learning and Collaboration research group at Oslomet – Oslo Metropolitan University, and other members of the group for their invaluable help in choosing the research method, and their useful feedback during the analysis process.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Figure 1 and table 3 were replaced due to drawing errors.

The reference to the table in the following sentence under Results was changed from table 3 to table 5:

We identified four main categories in the analysis: 1) pedagogical role, 2) academic role, 3) relational role, and 4) innovative role (Table 5)

Comments