How nurses and service users deal with malodour in the home

Some nurses say nothing about the problem of smell in order to protect the service user. However, the silence of the nurses reinforces shame and loneliness.

Background: Unpleasant odours in the home or emanating from a person are socially unacceptable and shame-related. Currently, little research has been conducted into how community nurses perceive and deal with unpleasant odours in their interactions with service users and how service users experience the nurse’s choice of action.

Objective: The objective of the study is to examine how nurses perceive and deal with the problem of smell in the home, and how the service users experience and view the nurses’ choice of action.

Methods: We carried out a qualitative study in which we observed and interviewed 30 nurses and 11 patients in three community nursing districts in a large Norwegian town.

Results: Unpleasant odours in homes were most often caused by illness and service users’ inadequate hygiene. The nurses regarded smell in the home as shame-related. They felt that service users were doubly vulnerable because both the person and the home were exposed to others’ disgust. They wanted to protect service users from feeling shame. The most usual strategies were removing smell through practical action, avoiding discernible physical reactions to smell, and keeping quiet about the problem. The service users felt that removing smells through practical action was important for their feeling of social confidence. Silence reinforced their sense of shame and loneliness, and sometimes contributed to a poorer range of treatment options. Service users wanted there to be more openness.

Conclusion: There is a need for more openness and expertise about the problem of smell in the home. It is important to ask about service users’ experiences and wishes in order to develop appropriate nursing and treatment options.

Community nurses must often deal with unpleasant ambient odours as well as malodour caused by illness. Smelling bad, or surrounding yourself with odours that are offensive to other people is generally regarded as socially unacceptable. This often leads to patients suffering because they are afraid of others’ disgust (1–8).

Meanwhile nurses find it challenging to be in patient-centred situations that involve malodour. This creates physical reactions such as grimaces, nausea, and a desire to withdraw from the situation (6, 9, 10). Malodour is also a difficult topic to raise with service users (11).

The studies we refer to here were conducted at a hospital or other institution. Research on how nurses perceive and deal with malodour challenges in relation to service users in their own home is limited. Moreover, there are few descriptions of how service users experience and view how nurses deal with smell in this context, and how service users want to be treated (12).

The objective of this article is to explore the problem of smell in the home, based on the following questions:

- What smells do nurses encounter in the home?

- How do nurses perceive and deal with unpleasant odours in the home when they engage with the service users?

- How do service users experience and view the nurse’s choice of action?

The article presents a sub-study that is part of a larger study, where the objective was to develop knowledge of how the community nursing service deals with the problem of smell vis-à-vis service users, and how the problem is dealt with as a job-related issue at workplaces (12).

Method and analysis strategy

We used an ethnographic design where the key concern is to describe what people say and do in situations that are not completely structured by the researcher (13). In the empirical survey, the fields incorporated three community-nursing districts and a private service-provider delivering home-based palliative care in a large Norwegian town.

We chose informants strategically, and 30 nurses and 11 service users participated. We recruited nurses following information meetings in the chosen fields. The inclusion criteria were at least two years’ professional experience where the problem of smell arose. Moreover, the informants had to be proficient in oral and written Norwegian. The nurses recruited the service users.

The inclusion criteria for service users were that they were over 20 years old and had had an illness for at least a year that entailed the problem of smell. They were required to understand oral and written Norwegian and to have the capacity to give informed consent.

We used participant observation and semi-structured interviews as methods. The observations and interviews took place in the period from autumn 2009 until spring 2011. The first author had the main responsibility for the data collection and analysis, in close dialogue with the co-authors.

Observation

The observation material included nine observations in nursing situations in the service users’ homes. We designed the observation guide with the aim of eliciting how nurses dealt with the challenges of smell in interaction with the users. The first author made field notes that included accurate situation descriptions as well as reflections on own reactions and methodological and ethical questions.

The interview material involving the nurses incorporated six focus group interviews and six individual interviews following observation of the nurses’ interaction with service users in their homes.

Interviews

The focus group interviews lasted between 45 and 75 minutes while the interviews following observation lasted between 15 and 25 minutes. All the interviews took place in community nursing facilities. We designed the nurse interview guide with the aim of eliciting their perceptions of smell in the home, their choice of action and their reasons.

The service user interviews were individual and incorporated seven women and four men aged 35–85 years with long-term malodour problems relating to wounds, infections and stomas. Cancer was the underlying diagnosis in the case of four of the informants. The interviews took place in the users’ homes and lasted between 15 and 55 minutes. We designed the service user interview guide with the aim of eliciting their experiences and wishes related to the nurses’ handling of the problem of smell.

Analysis

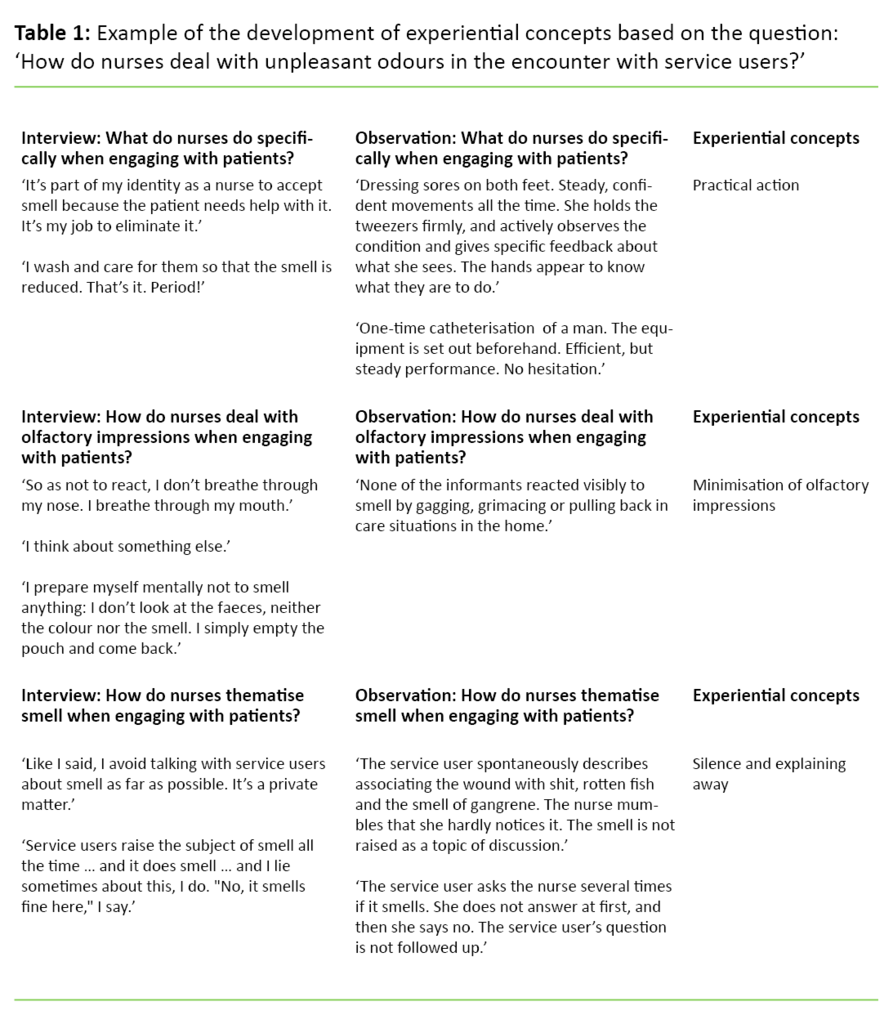

All the interviews were recorded and transcribed. In the analysis, we used an actor-oriented approach based on the informants’ statements and the researcher’s observations. Ideally, experiential concepts should be developed that reflect the informants’ perspectives (13) (Table 1). In line with the recommendations of studies that include different informant groups, we first undertook separate analyses of groups before the results were collated (14).

We commenced with a cross-cutting analysis of the field notes and interviews with nurses about what smells they encountered in the homes and how they perceived these. Then we examined how the nurses dealt with their perceptions in interaction with service users, and how they justified their choice of action. The informants’ answers reflected both their current and earlier experiences. We condensed the answers into text summaries with a focus on key points, differences, similarities and influential factors.

We then carried out a cross-cutting analysis of service user interviews about how they perceived the handling of the problem of smell, and what changes they would like to see. We condensed the responses into text summaries with a focus on key points, differences and similarities. In addition, we compared the service users’ experiences, reflections and wishes to the strategies employed by the nurses.

We discussed the findings in the light of sociocultural and nursing perspectives on how taboo and shame-related issues are handled in the Western cultural tradition.

Approval and consent

The project was reported to the Norwegian Centre for Research Data and approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REC) (application number S-09148d, 2009/1953).

We obtained informed consent in writing from the informants – both nurses and service users. Smelling bad is taboo and poses ethical requirements in relation to maintaining the informants’ integrity. Those who were asked to participate in the study received an information letter that clarified where nurses and service users could ask for help if they found that participation was burdensome. We received no such requests.

Results

Nurses’ perceptions and choice of action

Malodour in the home

A single, pervading disease-related odour could cause malodour in the home, for example putrid smells in the case of infections or cancerous wounds. It filled the entire home and camouflaged everything else. Complex constellations of odours were more common, in that odours connected with disease, the body and a lack of cleanliness in the home formed an indefinable combination:

‘And sometimes when you open the door of an apartment, a hotchpotch of smells hits you – from wounds, urine, faeces, cooking, rubbish lying around, and stale air.’

The nurses felt that unpleasant odours in the home were shame-related regardless of the reason. They also believed that service users who had these problems were doubly vulnerable because the smells not only affected them as individuals but also pervaded their space. Both the person and the home risked exposure to the disgust of others. At the same time, the unpleasant odours evoked physical reactions in the nurses in the form of grimaces, gagging and disgust.

The nurses lacked knowledge about the physiology of smell, and interpreted their own reactions in line with general cultural understanding as expressing abhorrence vis-a-vis the service users and their home. Such reactions on the part of the nurses conflicted strongly with their professional ethical commitment to safeguard vulnerable service users. This conflict created considerable moral anguish and a feeling of being unprofessional:

‘Sometime when you open a colostomy pouch, there’s an intense smell… And there was a cat darting between my legs. Then the cat vomited a hairball it had swallowed … And that’s the only time I’ve had to turn away and throw up. The patient was terribly upset, and I was terribly upset. Because I think it must be awful for that person to see that I am uncomfortable caring for him. And I think that I wasn’t being professional when I had to throw up.’

Strategies for dealing with smell

The nurses justified their choice of action by their wish to give the service user proper help and to protect them and their home against others’ abhorrence. For the most part, they employed three strategies:

One strategy was to reduce or remove the odours by means of practical actions addressing illness-related causes, for example through wound and stoma care, or assistance with personal hygiene. It was less common to remove whatever was causing the ambient smell because they viewed this as an inappropriate intervention in the service user’s home.

Another strategy was to minimise the olfactory impression so as not to react physically. The nurses used different techniques such as working quickly, creating physical distance in the care situation, holding their breath or breathing through the mouth. Facemasks were seldom used because of fears that service users would be offended. It was also usual to keep a mental distance by thinking of other things.

These techniques helped the nurses to avoid reacting physically, for example by grimacing gagging or showing disgust. However, the observations in the home showed that this strong focus on disciplining oneself physically resulted in several cases in impaired observation powers and reduced presence of mind.

A third strategy was silence and explaining away things, for example by saying, ‘I don’t notice anything, don’t think about it,’ if service users commented on the smell. The nurses believed that it would be offensive to initiate a conversation about smell. The fact that they were in other people’s homes reinforced this view:

‘I’ve never spoken to service users about smell … It offends patients if we talk a lot about it. Then I feel that the patients believe that we don’t want to do the job we do. So I don’t usually bring up the subject of smell.’

‘And then for our part, we’re going hometo people. We’re guests in other people’s houses. We can’t just blurt out this thing about smell.’

The nurses stressed that a lack of knowledge about smell perception and the absence of adequate language related to malodour were important reasons for their silence. One of them expressed this as follows:

‘You can say to someone else, “You look poorly today,” but you can’t say to anyone, “You smell bad,” with empathy.’

Service users’ assessment of the nurses’ choice of action

The service users’ experiences of and views on the nurses’ approaches varied. Practical action in terms of confidently performed procedures and the use of dressings and stoma equipment that reduce odour gave the service users a feeling of confidence. They greatly feared smells from the stoma, urine leakages and wounds. When the appliances were comfortable and well fitted, this reduced anxiety and resulted in people daring to participate in social situations to a greater degree.

However, several people expressed a deep-seated fear that their house might smell bad, not just them personally. The service users had rarely experienced that the nurses removed possible sources of offensive ambient odours.

Became insecure because of the nurses’ silence

The service users had little experience of or views on the nurses’ techniques to minimise smell. However, they reflected on situations where they had seen nurses react physically. One service user had seen that the nurse grimaced and turned away when dressing a wound. The nurse neither explained nor commented on these reactions. This created uncertainty in the actual situation and fear afterwards:

‘Because I’m now fearful – oh! For example, someone sat down beside me on the tram. And then he just got up and sat somewhere else. I just felt completely [face expresses consternation]: “What is it? Is it smell? Am I starting to smell again?”’

The physical reactions in themselves did not create the problem; it was the fact that they were not explained. The strategy the service users most objected to was silence on the part of the nurses. They wanted more openness generally. No one could recall that nurses had taken the initiative to talk to them in a professional manner about the problem of smell, or asked about their needs and wishes. Several of the service users said that they were aware of the odours themselves. They found the nurses’ attempts to gloss over the problem as lacking in respect.

‘No, but you know, almost all the nurses say that they don’t notice anything. … If I say when they’re changing the dressing: “Oh, ugh, that smell again”, they say that they don’t notice it so much. I don’t know if that’s meant to comfort me, or what? [Laughs a little.]. What about what I experience, then? Is what I experience plain wrong?’

The service users also use strong images to describe their own perceptions of smell: ‘When I notice the smell, I see myself as something hideous’; ‘The smell from the wound reminds me of a morgue’; or ‘Me and my home smell like rotten fish’. Everyone used swear words when talking about the problem of smell.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to explore how nurses perceived and dealt with unpleasant odours when engaging with service users in their homes. We also wanted to examine how the service users regarded the nurses’ choice of action.

The findings show that the smells in a home were diverse. They might be caused by illness or a combination of illness, body odours and unhygienic conditions in the home. A combination of smells was reported as most common. There are few contextual descriptions of smell, whether in relation to home-based nursing or in institutions. Therefore, it is difficult to relate the findings to other research.

The descriptions are not pretty, and clearly infringe social and cultural norms for how a home should smell and appear. The home should be clean and smell appealing and fresh. Sociocultural studies of smell show that offensive smells emanating from a person and home are associated with moral judgements. Pleasant smells are associated with the good and the beautiful – unpleasant smells with the bad, repulsive and immoral (15, 16). Waskul and Vannini’s study describes offensive smells in the home and emanating from people as low status and related to social exclusion (17).

Silence as protection against shame

The nurses saw service users living in foul-smelling homes as doubly vulnerable because both the person and the home were exposed to others’ disgust, which aligns with general cultural assessments. The nursing researcher Liaschenko terms vulnerability that affects both the person and their home as ‘spatial vulnerability’ (18). This expression conveys well the perceptions of the nurses and service users presented in this study.

The guiding principle in the nurses’ choice of action was acting in such a manner as to protect service users and the home from others’ disgust. They removed the smells through silently taking practical action without letting this affect them physically. These are general and conventional ways of dealing with shame-related and taboo matters (19).

They are also embodied in professional nursing literature that provides recommendations on how health personnel should exercise their professional and moral responsibility in care situations involving shame-related and taboo issues (20, 21). Practical action in combination with physical discipline and verbal reticence in the encounter with shame-related bodily issues has a long tradition in nursing. Having an inner sense of what the other needs without the service user having to say anything has been described as expressing respect, empathy and care (20–22). In this respect, the nurses acted in line with professional recommendations.

The service users wanted openness

Service users’ experiences showed that the nurses’ strategies functioned differently in respect of protecting the service users and the home from others’ disgust. Practical action in the shape of good wound and stoma care and assistance with personal hygiene were of basic importance in ensuring that service users felt confident when meeting others. Several studies refer to similar results (3–5, 23–25).

Unhygienic conditions and stale air in the home also caused malodour. The service users wanted nurses to speak more about this and put forward suggestions as to how to deal with it. The nurses were more reserved. They justified their choice by referring to the users’ autonomy and the fact that they were guests in someone else’s home.

The right to autonomy in the home is enshrined in Western culture (26–28) and is reflected in legislation (29) and the ethical principles of nursing (30). Emphasis on the service user’s autonomy in legislation and the professional nursing tradition can help to explain the reticence of nurses, but there is cause to ask whether their morally based choice of action reinforced the service users’ vulnerability in the home with respect to causing revulsion in others.

Strategies may have the opposite effect

The strategy of minimising olfactory impressions led to nurses avoiding visible reactions to odours, but it also entailed decreased powers of observation and reduced presence of mind. Accurate observations are fundamental to appropriate treatment, and presence of mind is crucial in creating good relationships. Disciplining the body in order to protect the service user from experiencing shame and disgust might therefore reduce the possibility of treatment and developing well-functioning relationships.

Nurses kept quiet and explained things away so as not to offend the users and their homes. However, the experiences of service users showed that this strategy had the opposite result. Silence reinforced their sense of shame and loneliness, undermined trust in their own perceptions and reduced the possibility of help. The service users called for greater openness in general.

The perceptions of service users and their wishes for openness about the problem of smell have not been systematically discussed in other studies. Therefore, it is difficult to assess how our findings relate to the problem of smell in other contexts. Silence can reinforce the sense of shame and loneliness and reduce the possibility of getting help. This has been documented in the case of other issues related to shame and taboos, for example mental disorders, AIDS and abuse. (31, 32).

Language taboos

A fundamental challenge linked to openness about malodour is language, as findings in our study also demonstrate. There are several reasons. The growth of a modern society with public sanitation projects helped to remove the smell of rubbish, decay, urine and faeces from public spaces and relegated these odours to the private sphere. Privatisation of these kinds of odours means that they are not part of a collective vocabulary to any extent, and the words used to describe them are negatively charged. Nor is there any publicly accepted discourse about how one talks about what is repulsive and unpleasant (2, 33).

This taboo makes it challenging for those who come from outside, in this case the nurse, to raise the problem of smell. There is a considerable risk of using words that might be perceived as disrespectful and stigmatising. In such situations, the service users’ own descriptions of smells are extremely important. They give an insight into how to verbalise culturally silent shame-related and taboo issues in a meaningful way. However, this requires the nurses to break their silence and enquire about the service users’ experiences.

Language is also related to knowledge. The nurses lacked fundamental knowledge about perception of smell, which explains reactions to unpleasant odours as autonomous, physiological reactions rather than as an expression of abhorrence of the person (34, 35). Knowledge of physiological causal explanations is important. It can help to reduce the nurse’s sense of shame when reacting and the disgust perceived by the person who is the object of such reactions. This may enable a more open and genuine interaction.

Limitations of the study

The sample of fields and informants is too small to be able to draw any general conclusions. Moreover, the fields have a limited geographical dispersion. The nurses’ assessments of vulnerability and choices of action might have been different if we had conducted the study in rural or heavily industrialised areas where unpleasant odours form a greater part of the public olfactory context than in this study.

Conclusion and implications for practice

The study provides an insight into the complexity of dealing with smell in the home. The findings indicate that malodour in the home makes the service users doubly vulnerable because both the individual and the home are exposed to others’ disgust. Established professional choices of action for nurses such as practical action, disciplining the body and silence functioned differently in terms of providing service users with adequate help. They perceived practical action as important, but questioned the silence and wanted more openness.

A lack of knowledge about smell perception and the absence of an appropriate language were key reasons for the nurses’ silence. The study indicates that strengthening nurses’ knowledge base regarding smell perception, asking about service users’ experiences and discussing smell perception in professional bodies is crucial for the ability to develop satisfactory help options for services users with problems related to smell. We need further research in this field.

We wish to thank Lovisenberg Diaconal University College and the Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, for having funded and facilitated this study.

References

1. Isaksen LW. Om angsten for den andres avsky. Inkontinens som et sosialt og kulturelt fenomen. In: Wyller T, ed. Skam: Perspektiver på skam og ære i det moderne. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget Vigmostad og Bjørke; 2001.

2. Isaksen LW. Om lukten og skammen. En historie om kroppens uorden. In: Gressgård R, Meyer S, ed. Fanden går i kloster: Elleve tekster om det andre. Oslo: Spartacus Forlag; 2002.

3. Lund-Nielsen B, Muller K, Adamsen L. Qualitative and quantitative evaluation of a new regimen for malignant wounds in women with advanced breast cancer. J Wound Care. 2005a;14(2):69–73.

4. Lund-Nielsen B, Muller K, Adamsen L. Malignant wounds in women with breast cancer: feminine and sexual perspectives. J Clin Nurs. 2005b;14(1):56–64.

5. Lindahl E. Striving for purity. Interviews with people with malodorous exuding ulcers and their nurses. Umeå: Umeå universitet; 2008.

6. Alexander SJ. An intense and unforgettable experience: the lived experience of malignant wounds from the perspectives of patients, caregivers and nurses. Int Wound J. 2010;7(6):456–65.

7. Lindahl E, Norberg A, Soderberg A. The meaning of living with malodorous exuding ulcers. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(3a):68–75.

8. Akhmetova A, Saliev T, Allan IU, Illsley MJ, Nurgozhin T, Mikhalovsky S. A comprehensive review of topical odor-controlling treatment options for chronic wounds. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2016;43(6):598–609.

9. Wilkes LM, Boxer E, White K. The hidden side of nursing: why caring for patients with malignant malodorous wounds is so difficult. J Wound Care. 2003;12(2):76–80.

10. Lindahl E, Norberg A, Soderberg A. The meaning of caring for people with malodorous exuding ulcers. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62(2):163–71.

11. Aranda S. Silent voices, hidden practices: exploring undiscovered aspects of cancer nursing. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2001;7(4):178–85.

12. Breievne G. Lukt og lidelse: fortolkning og håndtering av ubehagelig lukt i hjemmesykepleie. Oslo: Institutt for helse og samfunn, Det medisinske fakultet, Universitetet i Oslo; 2014.

13. Fangen K. Deltagende observasjon. 2. ed. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget Vigmostad og Bjørke; 2010.

14. Malterud K. Kvalitative metoder i medisinsk forskning. En innføring. 3. ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2011.

15. Corbin A. The foul and the fragrant. Odor and the French social imagination. Cambridge/Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; 1986.

16. Classen C, Howes D, Synnot A. Aroma. The cultural history of smell. London / New York: Routledge; 1997.

17. Waskul DD, Vannini P. Smell, odor, and somatic work: Sense-making and sensory management. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2008;8(No. 1):53–71.

18. Liaschenko J. Ethics and the geography of the nurse-patient relationship: Spatial vulnerabilities and gendered space. Sch Inq Nurs Pract. 1997;11(1):45–59.

19. Goffman E. Interaction ritual: Essays in face to face behavior: Chicago: Aldine Transaction; 2005.

20. Lawler J. Bak skjermbrettene. Sykepleie, somologi og kroppslige problemer. Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag; 1996.

21. Martinsen K. Løgstrup og sykepleien. Oslo: Akribe; 2012.

22. Nightingale F. Notater om sykepleie. Samlede utgaver. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 1997.

23. McKenzie F, White CA, Kendall S, Finlayson A, Urquhart M, Williams I. Psychological impact of colostomy pouch change and disposal. Br J Nurs. 2006;15(6):308–16.

24. Getliffe K, Fader M, Cottenden A, Jamieson K, Green N. Absorbent products for incontinence: ʻtreatment effectsʼ and impact on quality of life. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(10):1936–45.

25. Kelechi TJ, Prentice M, Madisetti M, Brunette G, Mueller M. Palliative care in the management of pain, odor, and exudate in chronic wounds at the end of life: a cohort study. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2017;19(1):17–25.

26. Martinsen K. Huset og sangen, gråten og skammen. In: Wyller T, ed. Skam: Perspektiver på skam, ære og skamløshet i det moderne. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget Vigmostad og Bjørke; 2001.

27. Angus J, Kontos P, Dyck I, McKeever P, Poland B. The personal significance of home: habitus and the experience of receiving long‐term home care. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2005;27(2):161–87.

28. Molony SL. The Meaning of Home. A qualitative metasynthesis. Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2010;3(4):291–307.

29. Forskrift 27. juni 2003 nr. 792 om kvalitet i pleie- og omsorgstjenestene for tjenestetyting etter lov av 19. november 1982 nr. 66 om helsetjenesten i kommunene og etter lov av 13. desember 1991 nr. 81 om sosiale tjenester m. v. Tilgjengelig fra: https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2003-06-27-792(nedlastet 21.02.2018).

30. Oresland S, Maatta S, Norberg A, Jorgensen MW, Lutzen K. Nurses as guests or professionals in home health care. Nurs Ethics. 2008;15(3):371–83.

31. Zerubavel E. The elephant in the room: Silence and denial in everyday life. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006.

32. Lauveng A. Unyttig som en rose. Oslo: Cappelen; 2006.

33. Skårderud F. Prestens løgn. Vårt Land; 2013.

34. Hawkes CH, Doty RL. The neurology of olfaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

35. Rouby C, Bensafi M. Is there a hedonic dimension to odors? In: Rouby C, Schaal B, Dubois D, Gervaris R, Holley A, eds. Olfaction, taste and cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University press; 2005. s. 140–59.

Comments