Pregnant women’s desire for private ultrasound examination in the first trimester

The women in this study wanted information and confirmation that their pregnancy was progressing normally in the first trimester. For them, a private ultrasound examination was a good investment.

Background: Ultrasound examinations in the first trimester have not previously been part of the antenatal care in Norway’s public health care service. Steadily more pregnant women are arranging to have a private ultrasound examination in the early stages of pregnancy.

Objective: To gain a deeper understanding of what motivates healthy women to have a private ultrasound examination in the first trimester of pregnancy.

Method: A qualitative design with an inductive approach was used in the study. We collected the data material from individual interviews with eight pregnant women. We used a semi-structured interview guide, and the data material was analysed by means of systematic text condensation.

Results: The women reported a lack of information from healthcare personnel in the first trimester. On the recommendation of friends and family, they arranged a private ultrasound examination in order to obtain more general information and to confirm the pregnancy and that the fetus was developing normally. The women wanted visual confirmation, and this strengthened their bond with the baby.

Conclusion: The women did not feel that they received sufficient follow-up from the midwife and GP in the first trimester. They considered a private ultrasound examination to be a good investment at a time when they were in great need of information and confirmation that the pregnancy was progressing normally.

Unlike other Scandinavian countries, Norway has not offered ultrasound examinations in the first trimester as part of the antenatal care in the public health care service.

Pregnant women with a known or increased risk of complications as well as women over the age of 38 have been offered prenatal diagnostic testing, which includes an ultrasound examination between weeks 11 and 13 (1, 2).

A report by the Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services (1) included a discussion on the public health care service supplementing the ultrasound in week 18 with an early ultrasound examination in week 11–13.

On 26 May 2020, the Norwegian parliament (Storting) passed an amendment to the Biotechnology Act, which meant that as part of their antenatal care, all pregnant women in their first trimester would routinely be offered ultrasound and an extra examination, which can reveal serious illness or fetal injury (3).

Technological developments and the introduction of 3-D imaging has led to an increase in ultrasound examinations, also for non-medical reasons (4). An ultrasound examination in the first trimester represents a milestone for many women and marks a new and safe phase in their pregnancy (5).

Women undergo private ultrasound examinations in order to obtain information about the health, development and sex of the fetus (6).

A Norwegian study (7) showed that women who were found to be at a low risk of fetal chromosomal abnormalities in an ultrasound examination in the first trimester, felt more reassured during their pregnancy, and developed a strong bond with their unborn child. The women also wanted to be prepared in the event that the examination showed developmental abnormalities.

Williams et al. (8) point out that some women want ultrasound screening in the first trimester so that they can terminate the pregnancy earlier if the examination shows serious fetal abnormalities.

A pregnancy represents a new and unknown situation over which women have no control. Øyen and Aune (9) report that understanding and care from healthcare personnel are important at a time when pregnant women feel vulnerable. GPs and midwives have the primary responsibility for antenatal care.

Pregnant women are free to choose whether they want to receive antenatal care from their GP or a midwife. However, the midwifery service is limited in many municipalities, which means that the service provision is often non-existent or insufficient to cover the demand (10).

A mismatch in the supply and demand in midwifery services has resulted in more private actors offering antenatal care in the last ten years (11).

In light of this, there has also been an increase in the number of pregnant women paying to take private ultrasound examinations in the first trimester. According to Hanger (12), over 70 per cent of pregnant women in Norwegian cities use this service.

Objective of the study

The purpose of this study was to gain a deeper understanding of what motivates pregnant women to take a private ultrasound examination in the first trimester of pregnancy.

Method

Data collection

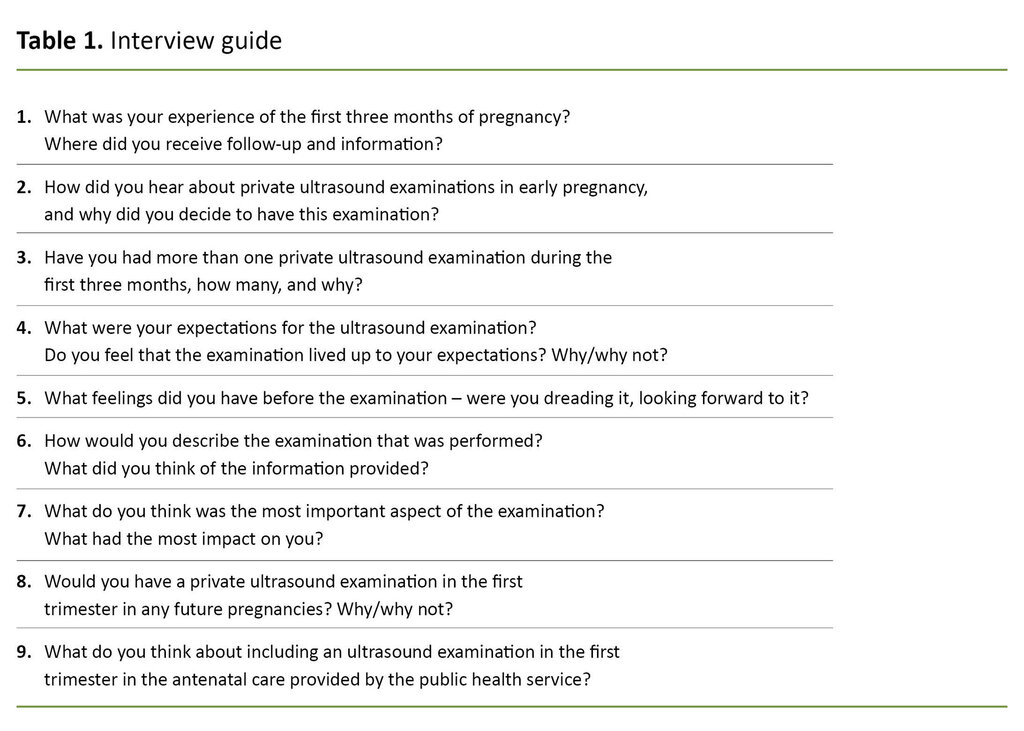

We collected the data material through qualitative interviews. Prior to the interviews, we prepared a semi-structured interview guide that consisted of questions aimed at gaining a deeper understanding of why pregnant women on their own initiative wanted to arrange a private ultrasound examination in the first trimester (Table 1).

Sample

Pregnant women from six different public health clinics in two Norwegian cities were recruited to the study. Midwives at the public health clinics distributed information leaflets to pregnant women at antenatal appointments. The women who were interested in participating in the study contacted the researchers themselves.

We emphasised that the participants themselves should choose the time and place of the interview. The inclusion criteria were pregnant women who, on their own initiative, had decided to have an ultrasound examination performed privately in the first trimester.

At the time of the interview, the women had to have undergone the ultrasound examination in week 18 and received confirmation of a healthy fetus. The women also had to be over 18 years old, speak Norwegian and not have undergone fetal diagnostic testing. The final sample consisted of eight pregnant women aged 27–35 years.

Four participants were primiparous women and four were multiparous mothers. Two of the women lived in west Norway, while the remainder lived in east Norway. All the women had a higher education and lived with a partner.

Ethical considerations

The participants signed a consent form prior to the interview. They were informed that participation was voluntary and confidential, and that they were free to withdraw from the study if they so wished.

We anonymised sensitive and personal data to protect the participants and reduce the risk of them being identified. The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (reference number 60678).

Data analysis

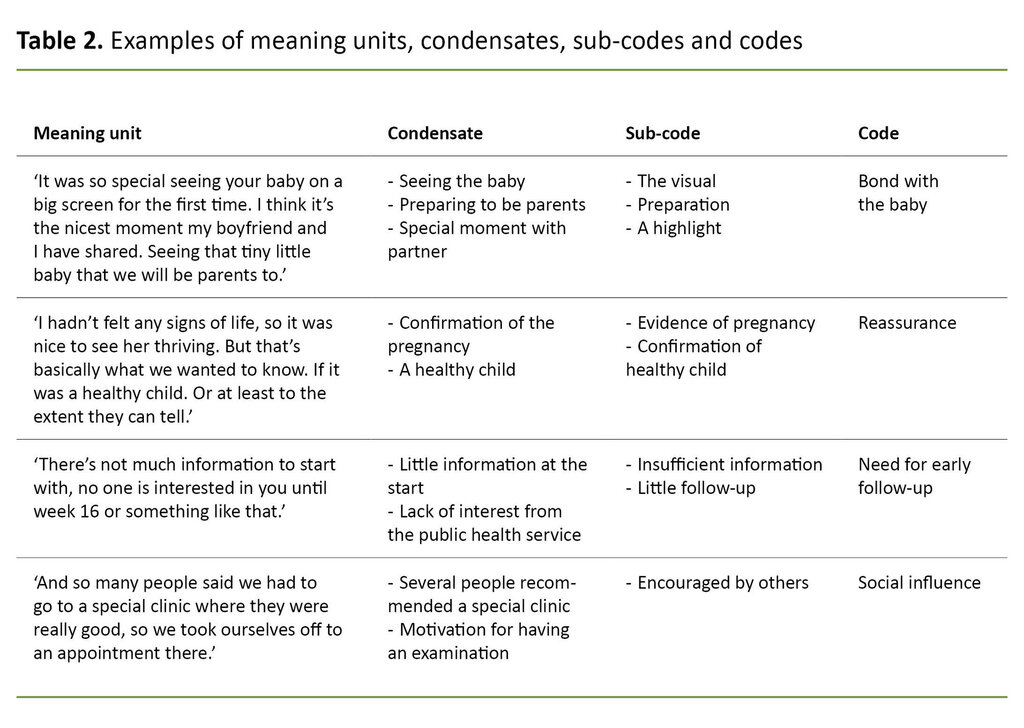

We recorded the interviews on audiotape and transcribed the recordings after each interview. The data material was analysed using systematic text condensation (13). In the first step of the analysis, we formed an overall impression of the material, and then formulated preliminary themes.

In step two, we systematically reviewed the material and identified meaning units that reflected the experiences and perceptions of the pregnant women. The meaning units were then sorted into groups and coded.

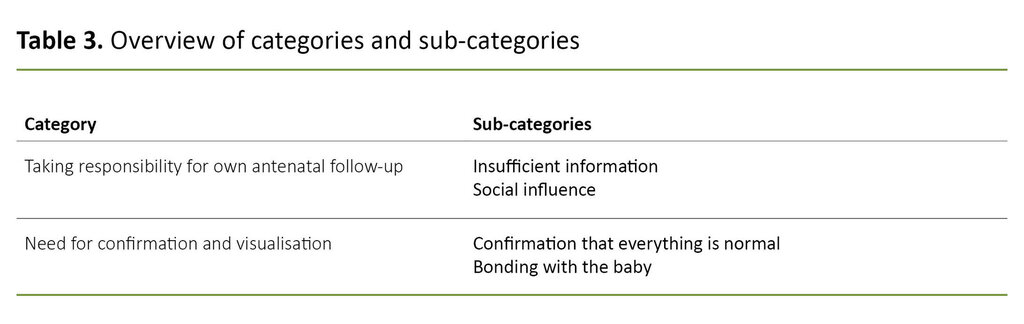

In step three, we sorted the meaning units into sub-groups, and each sub-group was reformulated into a condensate that summarised the sub-group in question. In step four, we wrote an analytical text for each condensate. Each of the code groups was then given a heading (Tables 2 and 3).

Results

Taking responsibility for own antenatal follow-up

The category describes the pregnant women’s experiences of receiving insufficient antenatal information from the GP and the midwife early in their pregnancy. Social influence had a large bearing on the decision to have a private ultrasound in the first trimester.

Insufficient information

The women explained that the first trimester was an uncertain time during which a number of questions and concerns arose about the pregnancy. Some of them read the books and brochures they were given by their midwife or GP, but most said that the internet, family and friends were the main sources of information.

The participants were aware that much of the online content is not written by professionals, and that the information is not always based on knowledge:

‘You search a lot online, and you see a lot of conflicting information […] You think you’re finding out things, but then you’re left with perhaps more questions than answers.’ (Tuva)

Some participants had to fight to get an early appointment with the midwife at the public health clinic.

The participants wished they had received more information from healthcare personnel at the start of their pregnancy. Several of the primiparous women did not know what the antenatal follow-up from the public health care service entailed, and not everyone was aware that they had the choice of going to a midwife or GP or a combination.

Some participants had to fight to get an early appointment with the midwife at the public health clinic. During that stage of pregnancy, they had a great need for information and had many thoughts and feelings that they needed to talk about:

‘I thought, my God, I’m not going to talk to anyone until week 12? I thought it was a long time to wait. Before that, I had no contact with anyone, really, other than listening to my own body.’ (Tone)

The women said that the quality of the information they received about the pregnancy at the first check-up varied, and they felt that it was a long time until the next check-up. They therefore sought out a private health care service and believed that the ultrasound examination was a good source of information in the early stages of pregnancy.

Several of the women said that the antenatal care in the public health care service should include an ultrasound examination in the first trimester, and that it should not only be offered to those in the risk groups.

The multiparous mothers’ decision to have a private ultrasound examination was based on previous positive experiences of this. These women would also choose a private ultrasound in any potential future pregnancies and would recommend the examination to others:

‘You find out that you’re pregnant in week 4 or 5, but then you don’t get a check-up from your GP until week 8-9, so you just have to sit around twiddling your thumbs while you wait to get into some system or other. So there’s plenty time to think and ponder on things in the beginning […] In that sense, I think that the offer of an early ultrasound helps to catch you at an early stage, when you need more information about how everything is progressing.’ (Elin)

Social influence

Most of the women were made aware of the private ultrasound examination through friends and family. Many had also read online that it was normal to have this examination, and they described the offer as an easily accessible service. Several of them felt obliged to have the examination performed to find out if the fetus was healthy and developing normally:

‘You worry that something might be wrong. And when you’re given good news, you can relax a bit. It’s never 100% certain, but at least you’ve done what you can to find out if your baby is doing well.’ (Siri)

Some women said that their partner took it for granted that they would have an ultrasound examination early in the pregnancy.

The participants explained that they decided to have their partner present during the private ultrasound examination to make them more included in the pregnancy.

Some women said that their partner took it for granted that they would have an ultrasound examination early in the pregnancy, and that this was part of the reason why they decided to have this examination:

‘There’s two of us in this, and this was when we would get to see the baby together for the first time. He took it for granted that he would be involved in this.’ (Siri)

Need for confirmation and visualisation

This category relates to the women’s need for predictability and reassurance early in the pregnancy. The category also describes the visualisation of the fetus, which marked the beginning of parenthood.

Confirmation that everything is normal

The women indicated that they felt a need for confirmation of the pregnancy in the first trimester. Some said they had few subjective signs of pregnancy, and they were worried, even though the pregnancy test was positive.

Several of the participants wanted an early ultrasound examination before informing friends and family that they were pregnant. Some were in poor physical shape during the first trimester. Visual confirmation of the fetus gave relief and reassurance and helped motivate them:

‘None of the things that you associate with a pregnancy are there. You don’t feel very pregnant. You don’t just trust a urine test. So it’s partly to do with getting confirmation that it’s there, and if it looks okay. It gives us reassurance that we’re actually pregnant.’ (Siri)

Some of the women reported having several private ultrasound examinations during the first trimester. This was because they had repeated concerns about whether the pregnancy was progressing normally and whether the fetus was healthy.

The participants described the first trimester as an uncertain time marked by anxiety and negative thoughts. Consequently, the women had an extra need for confirmation that everything was normal in the first twelve weeks:

‘It wasn’t enough with the one in week 8. It was probably because they can’t say very much at that examination, because they can’t see very much. So I calmed down for a while, but my concerns and overthinking started up again. It was easy to order another examination in week 12. Because I thought, at least this way you’re more sure that it will go well.’ (Ingrid)

Another reason why the women wanted a private ultrasound examination was to check that the fetus did not have any diseases or syndromes. Some participants said that they would have considered having an abortion if the ultrasound examination had revealed developmental abnormalities in the fetus, while others wanted to be able to plan for life with a child that was potentially impaired in some way. They pointed out that they would want to be given such news as early as possible in their pregnancy:

‘For us, it wasn’t necessarily about deciding about an abortion if the ultrasound revealed an unhealthy fetus, it was more about preparing to live with a sick child. Having plenty time to plan. If the fetus had been so unhealthy that you would have to have an abortion, you can do it in week 10 or 12 instead of week 20.’ (Tone)

Bonding with the baby

For the women, the desire for a visual image of the fetus was a major motivating factor for having a private ultrasound examination in the first trimester. They said it was a special moment that they were looking forward to with their partner.

The participants said that seeing the fetus early in the pregnancy was a very valuable experience.

They explained that they wanted to see who was ‘occupying’ their uterus, and that they thought it would create a stronger bond to the unborn baby. They emphasised that the visualisation and bonding would better prepare them for becoming parents:

‘It was so special seeing your baby on a big screen for the first time. I think it’s the nicest moment my boyfriend and I have shared. Seeing that tiny little baby that we will be parents to.’ (Siri)

The participants said that seeing the fetus early in the pregnancy was a very valuable experience. Several pointed out that once they received news that everything looked normal, they were able to relax and focus more on the visual experience of the examination:

‘After we found out that everything was normal, it was an even better feeling. We saw the baby for the first time, he shook his head and moved. It was magical.’ (Anita)

Discussion

The participants described the first weeks of pregnancy as an uncertain time with fluctuating emotions. The first trimester of pregnancy is a vulnerable time that is often marked by insecurity and anxiety (14).

Such psychological reactions are normal, but it is important to recognise and address them (15, 16). The women had a great need for information and sought knowledge via the internet, family and friends, brochures and books. They felt that they had little contact with the midwife or GP early in the pregnancy.

It is not uncommon for pregnant women to receive pregnancy-related information through channels other than healthcare personnel, and solely receiving written information does not improve knowledge to any great extent (17).

However, pregnant women read what they want and interpret written information based on their own coping strategies (18).

Early appointment can allay concerns

The participants felt that they had to wait a long time for their first antenatal appointment. They described how the concerns they had at the start of the pregnancy could have been prevented if they had had a conversation with the midwife or GP at an earlier stage.

Normal anxiety in pregnant women can be alleviated through good support and information from healthcare personnel (10, 19). They should therefore be offered an appointment as early as possible in the first trimester (10). They have the right to information about their own state of health and the health care they receive, as well as the right to decision-making involvement and participation (20).

The midwifery service is limited in many municipalities, and many women in the cities therefore use private health care services (12). The participants considered a private ultrasound examination to be a good investment at a time when they had a great need for information.

For the women in this study, the ultrasound examination in the first trimester gave them reassurance.

Ekelin et al. (21) observed that women feel less worried after an ultrasound examination. However, it is important that sufficient time is set aside for the examination, and that the information provided is adapted to the couple’s needs (22).

The women wanted information about complications that could arise during pregnancy. Being pregnant is an unfamiliar situation over which they have no control. However, pregnant women have a high level of trust in the health care service (23).

Before pregnant women undergo an ultrasound examination, they are often anxious that there may be something wrong with the fetus (24). This may reflect the growing trend of healthy, pregnant women who on their own initiative arrange for private ultrasound examinations in Norway (12).

For the women in this study, the ultrasound examination in the first trimester gave them reassurance, and this had a positive impact on their mental health during pregnancy. This is confirmed in other studies which show that when pregnant women feel reassured, they are able to regain control and are better equipped to deal with pregnancy (5, 7, 25).

A positive pregnancy test is not sufficient

The participants had few signs of pregnancy in the first trimester and did not consider a positive pregnancy test alone to be sufficient confirmation of the pregnancy. They therefore had a private ultrasound examination in order to get definite confirmation of the pregnancy, as other studies also show (5, 19, 25).

Women can have concerns about whether the fetus is developing normally. This is especially the case in the early stages of pregnancy when bodily changes are not yet noticeable (26).

Several studies show that women mark the time after the ultrasound examination as a new and safe phase in pregnancy. Once they are told that everything looks normal during the examination, they can start adapting to the role of parent (5, 9, 17, 27).

One of the major motivating factors for the participants was the visualisation of the fetus together with their partner. Women use ultrasound examination early in pregnancy as a way of being able to share the experience of pregnancy with their partner (19).

Visualisation and personification through an ultrasound examination also create a stronger bond with the fetus (7). Developments in ultrasound technology have led to an increase in ultrasound examinations, including for non-medical reasons (4).

Women feel that a private ultrasound examination is something that their partner, friends and family expect them to have. Social pressure of this nature can also be regarded as a factor in the normalisation of ultrasound examinations in the first trimester of pregnancy (7).

All pregnant women can now have an early ultrasound examination

This study was conducted before the new provision on universal early ultrasound examinations in the Biotechnology Act was adopted in May 2020. The participants wanted the ultrasound examination in the first trimester to be part of the antenatal care in the public health care service so that abnormal findings could be identified at an early stage.

Previous Norwegian studies show that women want to have an ultrasound examination in order to get information about the health of the fetus (9), and that an ultrasound examination in the first trimester should be a universal offer, and not just for those in the risk groups (7).

The participants’ experiences with the private ultrasound examination were positive and they would recommend it to others. It can therefore be assumed that such recommendations are contributing to the normalisation of private ultrasound examinations in the first trimester.

Weaknesses of the study

In this study, a small group of pregnant women shared their thoughts on private ultrasound examinations in the first trimester of pregnancy. The sample is therefore limited, and due to the qualitative design of the study, the women’s experiences are not necessarily representative of all pregnant women.

However, the participants spoke freely about the topic and provided rich and comprehensive descriptions that helped to give depth to the study and led to a greater understanding of the phenomenon being studied. All the women had a higher education and lived with a partner, which limits the transfer value of the study.

Conclusion

The women felt that the follow-up from the midwife and GP in the first trimester was insufficient. They considered a private ultrasound examination to be a good investment at a time when they had a great need for information and confirmation that the pregnancy was progressing normally.

The findings of the study illustrate that women need an appointment with a midwife or GP in the early stages of pregnancy to ensure they receive the care they need.

The authors would like to thank all the women for taking part in the study.

References

1. Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter for helsetjenesten. Tidlig ultralyd i svangerskapsomsorgen. Oslo: Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter for helsetjenesten; 2012. Available at: https://www.fhi.no/globalassets/dokumenterfiler/notater/2012/notat_2012_tidlig_ultralyd_v2.pdf (downloaded 23.01.2020).

2. Helsedirektoratet. Veiledende retningslinjer for bruk av ultralyd i svangerskapet. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2004. Available at: https://helsedirektoratet.no/Lists/Publikasjoner/Attachments/267/Veiledende-retningslinjer-for-bruk-av-ultralyd-i-svangerskapet-IS-23-2004.pdf (downloaded 23.01.2020).

3. Stortinget. Endringer i bioteknologiloven mv. Available at: https://stortinget.no/no/Saker-og-publikasjoner/Saker/Sak/?p=77395 (downloaded 13.06.2020).

4. Edvardsson K, Ahman A, Fagerli TA, Darj E, Holmlund S, Small R, et al. Norwegian obstetricians' experiences of the use of ultrasound in pregnancy management. A qualitative study. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2018;15:69–76. DOI: 10.1016/j.srhc.2017.12.001

5. Lou S, Frumer M, Schlütter MM, Petersen OB, Vogel I, Nielsen CP. Experiences and expectations in the first trimester of pregnancy: a qualitative study. Health Expect. 2017;20(6):1320–9. DOI: 10.1111/hex.12572

6. Thorup TJ, Zingenberg H. Use of ‘non-medical’ ultrasound imaging before mid-pregnancy in Copenhagen. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(1):102–5.

7. Aune I, Möller A. ‘I want a choice, but I don't want to decide’ – a qualitative study of pregnant women's experiences regarding early ultrasound risk assessment for chromosomal anomalies. Midwifery. 2012;28(1):14–23. DOI: 10.1016/j.midw.2010.10.015

8. Williams C, Sandall J, Lewando-Hundt G, Heyman B, Spencer K, Grellier R. Women as moral pioneers? Experiences of first trimester antenatal screening. Soc Sci and Med. 2005;61(9):1983–92. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.004

9. Øyen L, Aune I. Viewing the unborn child – pregnant women's expectations, attitudes and experiences regarding fetal ultrasound examination. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2016;7:8–13. DOI: 10.1016/j.srhc.2015.10.003

10. Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonal faglig retningslinje for svangerskapsomsorgen. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2018. Available at: https://helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/svangerskapsomsorgen (downloaded 23.01.2020).

11. Helsedirektoratet. Utviklingsstrategi for jordmortjenesten – Tjenestekvalitet og kapasitet. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2010. Available at: https://www.nsf.no/Content/362764/Utviklingsstrategi_J.. (downloaded 23.01.2020).

12. Hanger MR. Alle kvinner bør få tilbud om tidlig ultralyd. Dagens Medisin. 16. april 2018. Available at: https://www.dagensmedisin.no/artikler/2018/04/16/-alle-kvinner-bor-fa-tilbud-om-tidlig-ultralyd/ (downloaded 23.01.2020).

13. Malterud K. Kvalitative forskningsmetoder for medisin og helsefag. 4th ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2017.

14. Brodén M. Graviditetens muligheder: en tid hvor relationer skabes og udvikles. København: Akademisk Forlag; 2004.

15. Barba-Muller E, Craddock S, Carmona S, Hoekzema E. Brain plasticity in pregnancy and the postpartum period: links to maternal caregiving and mental health. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2019;22(2):289–99. DOI: 10.1007/s00737-018-0889-z

16. Brudal LF. Psykiske reaksjoner ved svangerskap, fødsel og barseltid. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget; 2000.

17. Lalor JG, Devane D. Information, knowledge and expectations of the routine ultrasound scan. Midwifery. 2007;23(1):13–22. DOI: 10.1016/j.midw.2006.02.001

18. Nicol M. Vulnerability of first-time expectant mothers during ultrasound scans: an evaluation of the external pressures that influence the process of informed choice. Health Care Women Int. 2007;28(6):525–33. DOI: 10.1080/07399330701334281

19. Gudex C, Nielsen B, Madsen M. Why women want prenatal ultrasound in normal pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27(2):145–50. DOI: 10.1002/uog.2646

20. Lov 2. juli 1999 nr. 63 om pasient- og brukerrettigheter (pasient- og brukerrettighetsloven). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-63 - KAPITTEL_3 (downloaded 23.01.2020).

21. Ekelin M, Svalenius E, Larsson A-K, Nyberg P, Maršál K, Dykes A-K. Parental expectations, experiences and reactions, sense of coherence and grade of anxiety related to routine ultrasound examination with normal findings during pregnancy. Prenat Diagn. 2009;29(10):952–9. DOI: 10.1002/pd.2324

22. Nicolaides KH, Chervenak FA, McCullough LB, Avigidou K, Papageorghiou A. Evidence-based obstretic ethics and informed decision-making by pregnant women about invasive diagnosis after first-trimester assessment of risk for trisomy 21. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;2(193):322–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.134

23. Hamre B. Svangerskapsomsorg. In: Brunstad A,Tegnander E, eds. Jordmorboka: ansvar, funksjon og arbeidsområde. Oslo: Akribe; 2010. p. 248–62.

24. Kowalcek I, Huber G, Mühlhof A, Gembruch U. Prenatal medicine related to stress and depressive reactions of pregnant women and their partners. J Perinat Med. 2003;31(3):216–24. DOI: 10.1515/JPM.2003.029

25. Hundt GL, Sandall J, Spencer K, Heyman B, Williams C, Grellier R, et al. Experiences of first trimester antenatal screening in a one-stop clinic. Br J Midwifery. 2008;16(3):156–9.

26. Ulvund I. Psykiske, sosiale og sosioøkonomiske endringer i svangerskapet. In: Brunstad A, Tegnander E, eds. Jordmorboka: ansvar, funksjon og arbeidsområde. 2nd ed. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk; 2017. p. 297–308.

27. Ekelin M, Svalenius E, Dykes A-K. A qualitative study of mothers’ and fathers’ experiences of routine ultrasound examination in Sweden. Midwifery. 2004;20(4):335–44. DOI: 10.1016/j.midw.2004.02.001

Comments